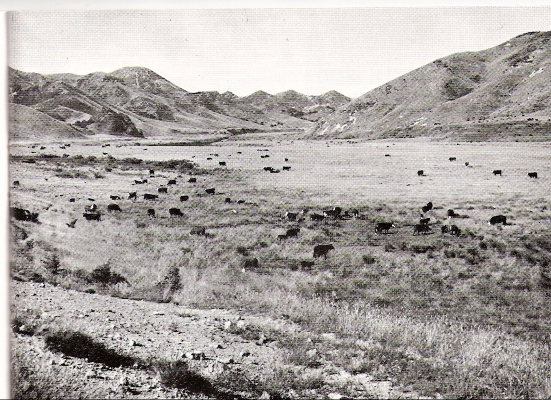

In the Clarence Valley. Photo: L. W. McCaskill.

Tussock Grasslands and Mountain Lands Institute Review, No 14, pages 17-20, March, 1968.

By R. W. M. Johnson, Agricultural Economics Research Unit, Lincoln College*

It is fortunate that the Department af Lands and Survey has kept very good financial records of progress at Molesworth. When these figures are viewed over the whole period since 1940, a most favourable picture emerges of good management, satisfactory economic returns, and soil control. This short article discusses a recent analysis af the Molesworth accounts and sets out some of the reasons why the results have been so good.

As is well known, the lessee of Molesworth surrendered his lease to the Crown in 1938, after a losing battle with low wool prices, rabbits and snow losses of sheep. In those days, Molesworth Station included the runs af Molesworth, Tarndale and Rainbow. Rainbow was re-leased in 1939, and the Lands and Survey Department first re-stocked the remaining two runs with cattle in 1940. In 1949, the lessee of St. Helens station - which included the St. Helens and Dillon runs - also surrendered his lease, and these two blocks were added to the above to give the present-day station area af 450,000 acres.

In 1949, cattle numbers had reached 2,500, and with the absorption af St. Helens the herd increased to 4,800. Numbers have slowly built up, and since 1959, the winter carrying capacity has fluctuated between 7,500 and 9,000 head of cattle. Further increases in numbers are limited by the need to provide adequate winter feed.

The main source of revenue to the station is the sale of two- and three-year-old steers in the Addington market. Prices have varied from $80 to $90 per head in recent years. In addition, the fairly steady level of herd numbers has meant that 400-600 heifers and cull cows could also be soId every year. Altogether, steers brought in a revenue of $92,000 in 1966/67, and cows and heifers brought in a revenue of $61,000 in the same season.

Molesworth is not a cheap station to run. Cattle replacements (mainly bulls) cost $15,000 per year, wages $20,000 and freight $8,000. The major item of expenditure is rabbit contro1, and in 1966/67 some $36,000 was spent on poisoning, aeroplanes, and rabbiters' wages. Since Molesworth lies outside a declared Rabbit Board area, the Lands and Survey Department can claim the usual rabbit subsidy directly from Government.

In this way, some $18,000 of the above rabbiting costs are recovered. The total running costs (including the full cost of rabbit control) comes to some $130,000 per year.

On the basis of present revenues and expenditure, the station has an annual surplus of about $50,000. This is the sum available each year for further capital expenditure. Interest has to be paid on money borrowed from the Treasury, but no allowance is deducted from the surplus for interest on the total capital worth of the property.

There are two measures of profitability which are worth calculating in the case of Molesworth:

(a) the rate of return on all money spent,

(b) the current rate of return on capital.

The first measure treats the enterprise rather like a Post Office savings account which allows withdrawals on overdraft as well as deposits. All current and capital expenditure is drawn out of the account, and all revenues are paid back in. As the enterprise develops, these revenues are expected to exceed the earlier costs of development. The question is, what rate of interest would these extra returns allow to be paid on earlier outgoings? The appropriate calculation shows that this rate of returns is 14.8 per cent, that is, the true rate of annual capital appreciation in the case of Molesworth has been nearly 15 per cent per year.

The second calculation shows present annual surpluses as a percentage of the total capital investment in 1966/67. This ignores the pattern of income and expenditure in the past and merely takes the present as a yardstick. If all development expenditure is deleted from the annual budget, it can be estimated that the true surplus as a going concern is about $60,000 per annum. The capital employed to generate this surplus is difficult to measure exactly, but on the basis of past capital expenditure of $200,000 and the present value of the cattle herd of $511,502, the capital employed is approximately $710,000. Alternatively, the Valuation Department's assessment of the value of land and buildings is $353,830, which gives a total of $865,332. These respective estimates give the following current rates of return:

On capital improvements at cost plus stock 8.4 per cent.

On capital improvements at valuation plus stock 6.9 per cent.

It can therefore be seen that the current rate of return in relation to capital employed is not spectacular, but nevertheless quite satisfactory for such a difficult type of enterprise.

The previous estimate of a return of 15 per cent reflects the fact that surpluses were probably higher in relation to the capital employed earlier in the development programme for Molesworth. This satisfactory result must be examined in the light of the history of the take-over of Molesworth by the Crown. In the conditions of the early forties, it was not at all clear that cattle could be made to pay on the high country; the decision to run cattle was made on soil conservation grounds as a possible answer to the depredations caused by rabbits. In conjunction with rabbit control, the improvement of the surface cover has been achieved by these means, and the decision has been proved a correct one. Indeed, over the intervening years a number of stations in the same area have now changed to an all-cattle policy.

The success of the cattle programme is also due to the high degree of adaptibility of cattle to the high country. In comparison with the excessive snow losses of sheep on Molesworth and St. Helens over the years the loss from deaths of cattle: over the last 27 years have been quite low (4.3 per cent). Apart from disease problems, the occupier's capital is not therefore periodically wiped out by factors beyond his control. The uncertainty associated with high-country grazing has been reduced.

A second factor contributing to the success of cattle on Molesworth is recent trends in world demand for beef. Over the years, beef meat has been in more demand than sheep meat, and fattening stock from Molesworth have received the benefit of this. In addition, the Molesworth stock have a reputation for doing well and quiet handling. Both factors have contributed to the economic success of the experiment with cattle in the high country.

The recovery of the surface cover has not been without its problems. The growth of sweet brier is one of these. Apparently cattle are more fastidious than sheep or rabbits and will not nibble the young brier shoots down. At some stage control of brier could be quite expensive.

The skilled management of Molesworth has played its part. Mr Chisholm has built up a tremendous knowledge of the problems associated with high-country grazing with cattle, and the results so far outlined together with the excellent lines of steers seen in the Addington saleyards are good testimony of this.

Under the circumstances, it seems unlikely that these results could have been achieved by private run-holders. The role of the State has been to provide a large amount of capital in a period when the economic future was uncertain, and the particular success of cattle as a grazing animal in the high country was unknown. The soil conservation objectives of the experiment are being achieved. It is the value that the community places on these objectives that will determine the future role of the State in the high country. If the technical needs of soil conservation are rated high enough by the community, then large-scale destocking of the high country of sheep may be necessary. In this case, a great deal of re-organisation will be needed in boundaries, fences, buildings and finance. It is likely that the State would then have to step in, in a paternal and beneficial way, to ease the many difficulties of the transition and change to a full soil conservation programme.

* Mr Johnson is the author of the recently published "High Country Development on Molesworth," a 35-page economic survey of the property, Publication No. 40 of the Agricultural Economics Research Unit, Lincoln College.