by R. W .M. Johnson

Ministry of Agriculture, Wellington

This paper explores the application of property rights to sustainable land management objectives. Property rights are briefly defined and discussed in terms of their characteristics including the principles of attenuation and efficiency. Their relationship to the Resource Management Act is then discussed in the context of its sustainability objectives. The future development of suitable regulations and incentives is assessed from a property rights point of view.

The chosen system for achieving changes in farm management practice in terms of soil conservation objectives has been to offer a system of incentive payments to land holders targeted on needed conservation objectives. These incentives recognised the strong bargaining position of the landholders both politically and legally. Their political power stemmed form their dominance in the early legislatures while their legal power stemmed from the system of land registration first introduced by Torrens in South Australia. The thrust of the argument to be presented here is that the Torrens system was too successful in achieving its primary objective of title security and lacked the flexibility to be adaptable to needed changes in practice when these became necessary in the pursuit of wider environmental goals.

This paper first discusses the nature of property rights with specific reference to land holding and defines what is regarded as an efficient set of property rights. Reference is made to how water and mineral rights relate to these attributes. The paper then goes on to examine a proposition that a re-distribution of land property rights toward social ownership would be an alternative method of reaching needed land management standards at considerably less cost to the exchequer. This proposal is compared with other polluter pays proposals for meeting conservation goals. The paper concludes by assessing how practical these propositions are and whether they are technically achievable.

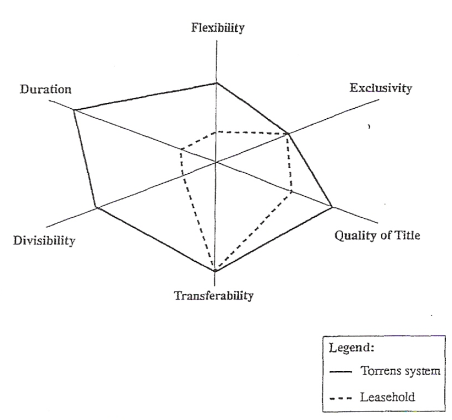

Figure 1: Six characteristics of interest in real property (after Scott, 1989).

| Comparison of Tenure Systems | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Torrens System | Leasehold |

| (Scores on a scale 0 - 100) | ||

| Duration | 100 | 20 |

| Divisibility | 80 | 20 |

| Transferability | 100 | 100 |

| Quality | 100 | 80 |

| Exclusivity | 50 | 50 |

| Flexibility | 80 | 20 |

Property rights are a set of behavioural rules that society chooses to observe and accomodate to. Dragun (1989) refers to "the social pattern of rights and duites". They can be established through custom, convention or law (Hide 1987). The essential fact is that they are observed rather than sanctified by law alone. In land holding such rules specify who may use a resource and how the resource may be used. SUch rules allow exchange to take place with some security and therefore assist in allocating resources among competing interests. The market works precisely because it is backed up by a set of property rights.

Exchange of property rights is based on their exclusivity and transferability. An exclusive property right is the ownership of a car; a common property right is the right to use the roads. One is exclusive and transferable and one is not. The right to exclude, says Hide, is a pre-condition to the right to trade. An exchnage permits a value to be established and hence establishes a market fro property rights. Exclusive propert rights must be specified and policed, and contracts for the exchange of rights must be negotiated and enforced.

There are at least six characteristics of property rights that qualify their usefulness in economic exchanges (Scott 1989). A recent reference is Young (1992) who discusses sustainable investment and resource use from a similar point of view. Figure 1 shows a diagrammatic representation of these of these six characteristics of interest in rights which are based on the following descriptors:

Flexibility: discretion to change use; ability to adapt to change; what can and cannot be done without consulting others.

Exclusivity: the strength or a right; the inverse of the number of persons who must be contacted to internalise enterprises like fishing (Scott); freedom from disturbance; strength of acceptance by the community; exclusive entitlement to profit (Young).

Quality of Title: legal protection and security provided by common law and things like registration systems; acceptance of title by others; political stability, right to compensation, right of first refusal of any new set of rights (Young).

Transferability: ability to transfer to others; number of parties to whom a transfer can be made (Scott); movement to morE equitable and more ecologically appropriate locations, combinations and uses (Young).

Divisibility/Assemblability: ability to sub-divide; ability to aggregate; ability to share; ability to have joint holders (Scott); ability to assist transferability (Scott); usefulness of small bundles (Young).

Scott then says the amount of each characteristic in a standard interest can usefully be regarded as observable, measurable and continuously variable. For example, each may be scored from 0 to 100. This classification is intended to replace terms such as "incomplete", "imperfect", "attenuated", or "property-ness". Furthermore, these characteristics can be regarded as a sixpointed star-shaped figure formed by joining its measured points on the six characteristics axes. This is what is shown in Figure 1.

It is possible to use such a diagram to compare two systems of land rights. In Figure 1 a freehold system of land tenure is compared with a leasehold system. The right to occupy land is well understood in New Zealand. Fairly arbitary scoring on the 0 to 100 scale has been used for this example. But in general, freehold systems of land tenure are very high on most attributes other than exclusivity (there is not a lot of protection from the actions of others) while leasehold tenure scores weakly except on transferibility and quality of title. The resulting linkages between characteristics in the diagram thus form "pictures" of different property right systems. Young (p.110) maintains that a continous lease or licence framework is a promising way of achieving environmental security through roll-over and compensation clauses.

An alternative formulation to Scott's characteristics can be developed through the concept of attenuation (Quiggin 1986) . Any limitation on the way in which property rights may be used constitutes attenuation. The ideal, unattenuated state is approximated by private chattel ownership where the owner has completely free rights of use, exclusion of all others and complete alienation. The attenuation of property rights, in this view, will always reduce their value to the owner, and is sometimes viewed as undesirable (ie by the followers of Coase). This is particularly true when attenuation is the result of actions of governments, such as regulatory limits on the way in which property may be used or restrictions on the sale and purchase of property. The key features of non-attenuation are complete specification of the right, exclusive specification, full transferibility and enforcibility (Dragun 1989).

However, as Jacobsen (1991) points out, the ownership conferred by property rights does not normally entail the right to impose costs on others. Rights are attentuated by the state to prevent adverse consequences to others, and in turn protect owners from the actions of others. For further discussion of the philosophical origins of these terms see Alchian and Demsetz (1973), Castle (1978), Quiggin (1986), Izac, (1986), Cox, Lowe and Winter (1988), and Dragun (1989) among others.

An efficient set of property rights refers to minimising the costs of making changes to right holdings, the costs of policing and the costs of establishment (eg registration). Hide (1987) gives an analysis of transaction costs and their relation to efficiency. Young (1992, p 112) also recognises the role of cost effective administration. The Torrens system of land registration is a very efficient set of property rights because it provides high security at low registration cost, it requires low policing costs and changes can be made at small cost and easy convenience. Litigation raises the costs of many exchanges of land rights and hence can be seen as a counter to transaction efficiency. Poor design in legislation could be one reason for this. Thus an efficient set of property rights is a well designed set, widely trusted by the people involved and not subject to vexatious litigation. Conflict does arise, however, and the courts may be the only way to resolve difficulties between conflicting interests.

There is some conflict in the literature with this definition of efficiency. Bradsen (1988) for example does not distinguish between project costs and transaction costs and hence never really defines what economists would call an efficient system. Jacobsen (1991) discusses social cost-benefit analyses incorporating the depreciation of natural capital as a cost. Subsequent discussion indicates that Jacobsen includes transaction costs, such as "high costs of public ownership", within her definition of social cost.

There are thus two efficiency goals to consider. Attenuation of property rights may be required to achieve a social optimum in a resource use problem area where externalities are present. This would include, for example, developing institutions which recognised the appropriate shadow prices and facilitated socially optimal solutions. Secondly, efficient use of property rights as an institution can be achieved by good legislative design and appeal systems. This latter objective necessarily includes the regional or local government bodies which will administer the legislation.

We have well-developed and efficient sets of property rights for land. Freehold title is generally regarded as more secure than leasehold title. The system is so well designed that it provides full security at low cost, has low policing costs and provides a high degree of protection. The market for land operates without any doubt as to the authenticity of the title or the potential risks.

The right of ownership then confers on the owner further rights as to how he/she might use that right. They may prevent trespass, they can choose any land use they like, they can erect a building and they can sell any product from that land without encumbrance. ("Use" is defined in the town planning sense rather than a farming sense). Titles can have attachments to them such as the registration of debt secured against that title. In Western Australia, notices to occupiers of land from the commissioner of soil conservation can be registered with the appropriate land registrar (Looney 1991). Some attachments lower the exchange value of a right but at the same time inform the players in the market and therefore raise efficiency.

Security of a right is generally associated with a greater commitment to long term care of the land. Figure 1 explains this difference from the point of view of the various characteristics of interest in a right. Against this we need to consider Young's view that leasehold tenure may have the potential to adjust to changing circumstances.

The rights of use have become constrained by social controls in a number of instances. The Town and Country Planning Acts and mineral legislation, for example, constrain building rights, subdivision and access typically. They do not constrain the selling of the product, however, though cases of this do occur (see indigenous forest discussion below for example).

In the historical context, these property rights facilitated the opening up of the land. They provided an incentive to develop and enabled the developer to capture all the gains from occupation. They also secured the owner a reward when development finished as the right was immediately transferable to others at a market determined price backed by the very system of which it was part.

In the longer run, it was inevitable that some of the (social) costs of development of the land were not captured in the market process. In particular, deterioration in surface cover, soil loss, sediment transmission, and water quality loss can still occur within the Torrens system of land registration, which was otherwise so efficient in achieving its purposes. The conditions of use of the right allowed these things to happen and no sanctions were introduced to prevent them happening for a long period. The position was potentially worse where leasehold land was concerned (Kirby and Blyth 1987).

When changes (in externalities) take place or new ones are recognised, the system of property rights is no longer efficient and efficacious. A new system of property rights is needed to reflect societal values which at the same time minimise transaction costs. The Resource Management Act epitomises the new set of social values and indicates that both regulatory and market based measures may be used to reach the Act's objectives. Such legislation must be scrutinised very carefully from the property right point of view just because new solutions and the consequential legal provisions could potentially be very expensive or vexatious to introduce or bring about.

In economic terms the Torrens system does not deal well with environmental externalities. Soil erosion, seepage, and water contamination are the long term impacts of the human use of land which affect others than the right holder. They occur as a result of the inability to negotiate and enforce an exchange of the relevant property rights (Hide 1987). The inability arises because physical or technical factors prevent the parties getting together or they simply went unobserved. They are typically nonpoint sources of degradation.

In the case of waterborne sediment, the downstream owner's rights are not protected; there is no market in "rights to cause soil loss" and transfer the costs; there is no point discharge on which to fix a levy; solutions up to the present have been based on incentives to degraders to stop or control the relevant practice. One solution is to bring the degraders and the recipients together in a common rating system and spread the costs of treatment; in this way the externality can be internalised.

Legislation like the Resource Management Act can be viewed as an exercise in the redistribution of property rights. Legislation places restrictions on the use of resources governed by property rights and hence can potentially change land use itself. An attempt to change access rights for mining exploration is discussed below.

The scope of such legislation is also governed by property rights. By scope, is meant all those persons and corporates who may be affected by the provisions. Control over resources means control over the users of resources. The users are already in occupation and have established formal and informal rights. The domain of such legislation is defined as being all property held under some system of rights whether it be freehold land (registered title) or some other right conferred by custom, agreement or contract. Thus there is no reason why good practice standards should not be introduced for leasehold land as well as freehold land.

Property rights are important in land precisely because they enable social control over resource use and management (Hide 1987). Through reform and adaptation, the use and management of resources is improved. In adapting property rights, society adjusts the respective roles of the state and the individual and explores the ability of political and market mechanisms to manage the resource stock better to reach the desired social optimum.

Water rights are an example where social considerations often outweigh the desires of the individual. Riparian rights derived from prior access have given way to appropriation doctrines that consider water a public resource held in trust by the Crown (OECD 1987). Permits or licences are used to allocate the resource thus substituting administrative procedure and/or legal covenants for a market in single use rights. Current criticism is based on the imperfections of such administ:rative systems as they do not adequately provide for recreation, conservation and spiritual values, do not provide for other water uses, and do not provide an efficient set of rights (Moore and Arthur-Worsop 1989).

This viewpoint maintains that a system of well-defined and tradeable property rights would be more socially advantageous than administered systems. They could provide greater flexibility and security, better information on resource values, minimal transaction costs and the ability to accomodate new resource values (Hide 1987). Flexibility comes from being able to allocate water in accord with demand and changing use values. Security is gained by actual ownership of the right, as opposed to Crown ownership. The allocation process has the potential to be more transparent as resource values will emerge through bidding among alternative users. In a well-defined statutory environment information regarding transfer arrangements and possibilities is more transparent thus limiting uncertainty and ultimately transaction costs. These conclusions are consistent with a movement towards non-attenuated rights as defined earlier.

Administrative systems hide or disguise transaction costs. From an economic point of view achieving an efficient set of water property rights should be the target of public policy. A market for water rights creates opportunities for new uses to be recognised at relatively low cost. It would probably not provide for all recreation, conservation and spiritual values unless the respective lobbies were forced to "buy" their requirements. However, investigating, assessing and verifying all claims to a water source (not to mention appeals and legal proceedings) remains a high transaction cost process. Therefore legislative solutions in water rights must be particularly well-designed to achieve the potential efficiencies that are possible.

It has been pointed out that water markets will not perform perfectly (OECD 1987, Ch 2). Market based allocations may not recognise the proper.social accounting (or shadow) prices. In a multiple resource use situation, some uses will be difficult to identify and measure, and the mix of private and public goods will greatly complicate the design of an efficient property rights system. The presence of some public good aspects in the solution will always lead to some under-statement of demand.

Under the Resource Management Act, we are in a position to move to a system of transferable water permits. The responsibility for implementing them will fallon regional councils who will establish the regulatory and allocative framework for granting in-stream rights. Further analysis is obviously needed of these institutions to ascertain the relative efficiency of different allocation systems.

In this section access and product disposal rights are discussed. Under New Zealand mining legislation the surface owner has a right of veto over access on certain classes of land only. These classes include land under some horticultural use, land in urban areas, land under burial grounds, airstrips, waterworks, roadS, bridges or buildings, and all conservation land. The remainder is open to access (for exploration) without consent of the owner and makes up most of the pastoral farmland and exotic forest estate. For information on other mineral property rights see Jardine and Scobie (1990).

In the Resource Management Bill, it was proposed that land owners should have a veto over prospecting, exporation and mining on all land. In the past the mining rights had over-ridden the occupation rights. The proposed veto changed the distribution of property rights and hence the incentive to invest and develop. Such a veto would discriminate against the Crown as a mineral and petroleum owner in favour of the landholder. It would also reduce the incentive to explore for minerals and raise the transaction costs of getting access. This would reduce the efficiency of the set of property rights held by the explorers. It would transfer windfall gains from the former owners of rights (the explorers) to the new owners (the surface owners) and could result in a lower rate of mineral exploration and hence affect the over-all development of the economy.

This is case of the relative efficiency of two right systems. From the point of view of the landholder he is interested in getting rid of (mining) rights that have priority over the ones he holds. From the point of view of the explorer, and indeed of the nation, the status quo was all about enabling society to have it both ways; one use of the land can continue to be developed while the potential to use it for something else is not forgone. Environmentalists had sided with the landholders in the debate as they wanted greater impediments to mining development as an absolute goal. In the event the status quo was preserved in the Crown Minerals Act and further testing and analysis of the relative merits of the two systems of property rights was passed over.

The disposal of product derived from the possession of a right 1S exhibited by the regulations prohibiting the felling of indigenous trees for export purposes. The regulations were part of an attempt to conserve the native forest estate as well as trying to conform to international standards of behaviour with respect to the felling of indigenous forests.

The ban on exports effectively used an administrative decree to limit the harvest of trees on private land. The regulations prevented landholders from felling timber for export purposes without compensation. Thus the surface owners interest in the land was made subservient to the public interest.

From the landholders point of view here was an arbitary decision to limit the sources of his income. It appeared there were cases where the exploitation of this resource was essential to the continued viability of the individual enterprise. Subsequent negotiations recogised this fact and a form of compensation was agreed to. The new government elected in 1990 has since put the forest regulations on hold.

From the environmental point of view it was regarded as imperative that New Zealand made an international gesture as early as possible.

From an efficiency point of view, the proposal was disadvantageous for the land right holder. The plan would have involved the preparation of a sustainable harvest plan approved by the Ministry of Forestry. The costs of this plan, especially if it involves survey costs, could make this option non-operable for many smaller freehold areas of forest. Some discussion was also based on the introduction of a felling fee to discourage use of the private forest estate. In all these cases the transaction costs of the conservation goal would have been high.

The Resource Management Act is effectively a change in the social paradigm that directs land and water resource use. The concept of sustainability lies at the centre of the Act's provisions. In the Act sustainability is defined as:

"...managing the use, development, and protection of natural and physical resources in a way, or at a rate, which enables people and communities to provide for their social, economic and cultural wellbeing and for their health and safety while:

a) sustaining the potential of natural and physical resources (excluding minerals) to meet the reasonably foreseeable needs of future generations; and

b) safeguarding the life-supporting capacity of air, water, soil, and ecosystems; and

c) avoiding, remedying, or mitigating any adverse effects of activities on the environment".

The Soil and Water Conservation Act was passed in 1941 and the Town and Country Planning Act in 1948. These Acts have gradually introduced definitions of what could be called "good" land and water use and provided mechanisms for national and local government to pursue such goals. The legislative provisions impose restriction on the holders of land rights and represent reductions (or attenuations) in the earlier property rights granted to them, bought by them, or inherited by them.

In general, the cooperation of landholders (in soil conservation particularly) has been gained by a system of incentives for changes in management practices. As earlier mentioned, common law rights to water were abolished by the Water and Soil Act 1977 and control shifted to the State. Subdivision, changes in use (including buildings), and peri-urban development were all "licensed" under the town and country planning regulations. In the new Act, local government will be responsible for amending or continuing the ordinances which will have higher standards to meet than in the past.

In broad terms the experience in soil conservation has only been partially successful. There would be some sympathy for the view that "Australia's departure in the 30s and 40s from the Australian way of dealing with land management problems, such as pest plants, animals and insects, to rely on the US voluntary, awareness, education, approach to land degradation can perhaps be excused,...It has not been effective and continued reliance on this approach cannot be excused. The commitment of substantial community funds compounds the error, especially in the absence of accountability according to proper land conservation standards" (Bradsen 1989, p 11).

Without using property rights language, Bradsen is in favour of strong attenuation of land use rights to eliminate externalities and meet desired standards. He recommends compulsory property plans incorporating sustainability principles. This would be backed up by some system of enforcement, including the power of aquisition, an appeal system, and provision for formal reports and periodic reviews. Landholders should, for a period of adjustment, not be required to meet all costs on a polluter pays basis; considerable sums of Commonwealth finance will be required.

Thus Bradsen's emphasis is on compliance and standards and the means to best achieve these. There is no accounting of transaction costs of the alternatives. It is essentially goal driven. This example is useful as it provides the extreme case in the following discussion of less attenuated systems for achieving the same objectives.

Over a considerable area of land conservation, and particularly for soil conservation, systems of cash incentives have been used to encourage good land management practices. This system of subsidies and concessions is necessary, say Bromley and Hodge (l990), to counter-balance the existing set of property rights. They see the state becoming more and more involved with technological externalities of existing land use practices as the state represents the section of society affected by the unwanted effects of agricultural land use. The state's response has been either to introduce some form of regulation in which specific quantitative goals will be set, or a set of financial inducements to obtain compliance from the agricultural community. The process is accompanied by extensive political negotiations in either case. In effect, say Bromley and Hodge, the presumed property rights in land become translated through the political process, into presumptive entitlements in the policy area (see also Cox, Lowe and Winter 1988).

But such arrangements need not be fixed in concrete; "The presumption of an absolute right to produce food and fibre creates an open-ended agricultural policy in which the state - and its treasury - has become the captive of the sancity of private rights in land, the political power of the farmers, and the technological prowess of modern agriculture. If farmers are on a technological treadmill, the industrial state is surely on a fiscal treadmill. The generally secure position which landowners enjoy, however, has no immutable legitimacy - though its political legitimacy is another matter. Institutional arrangements are social creations, fashioned to serve collective objectives" (Bromley and Hodge 1990, p 212).

Bromley and Hodge propose an alternative approach. They suggest that the state defines a desirable system of land use compatible with environmental objectives, and that existing practices be measured against this desirable system. "The desired level of countryside and community attributes would be determined through collective action at the local level, but with wider oversight if the domain of concern transcended the locality" (p 202). A plan for a particular area would specify the constraints over land use required to achieve the desired level of environmental quality. Farmers would remain free to choose enterorises and methods of production so long as the final result does not violate the plan. In effect, the property rights which formerly resided with the farmer are transferred to the collective entity.

To make the system flexible, it is suggested that the farmer be given a right to deviate from the plan by paying into the public purse. This represents a turnaround of the incentive system where the farmers bribe the state rather than the state bribing the farmers. It is a variation of the polluter pays principle. The deviation from the standard would presumably lead to greater private income from that permitted and hence would be a source of the payments that would flow to the state. The farmer would have to weigh up the alternatives. If instituted, such a system would reverse the direction of payments from the traditional pattern.

The authors discuss the administration of such a system of property rights. A considerable administration would be required in terms of specifying the appropriate constraints for the various regions of a country, and in systems for assuring compliance. The mix of environmental objectives could be quite wide and complex and would differ for different regions. In our case, a new set of goals and standards would need to be evolved. Point sources would be easier to accomodate than non-point sources. A considerable scientific input would be required (though there are similarities here to Bradsen's approach). Current legislation would have to be re-drafted to meet the holistic systems approach put forward.

The proposed system would bring about a realignment of all the incentives to produce. Policy instruments that give financial incentives to farmers would disappear. Production levels would be governed by the system of permits which allowed deviations from the ideal (Bromley and Hodge assume that the ideal is not at the top of the production possibility curve). Generally, output would be most modified where farming systems were heavily dependant on sensitive environmental inputs.

The costs of production would be higher (except in the case of zero use of environmental inputs if such could be found). Costs would increase either to meet the new standards or in bribing the authorities to get departures. Output positions would depend on the particular effect or each environmental constraint. It seems plausible that the costs of meeting the standards would depress the value of the land right and hence land values; the higher the standards are set above practice the lower the resulting land value.

Finally, agricultural producers would come to be regarded as land managers rather than producers. If increased costs drive up market prices for products, then consumers would be paying a tax for product produced in an environmentally sound way. This would be an estimate of the social cost of current agricultural practice. If the complete system were to be accepted and to be instituted successfully, the environmental externalities of existing agricultural systems would have been internalised.

In terms of current land tenure systems the proposal seems a very large step into the future. There are various practical problems which are discussed below. However, Bromley and Hodge remind us that nothing is immutable; "It is important to recognise that the current assignment of of entitlements in land and, by extension, in the policy arena - are simply artefacts of previous scarcities and priorities, and of the location of influence in the political process. To assume that these entitlements are necessarily pertinent and socially advantageous to the future is unwarranted. Shifting values and changing perceptions of the role of agriculture will surely bring about at least marginal shifts in property rights and policy entitlements"(Bromley and Hodge 1990, p 212).

The above discussion demonstrates that any system of reform of property rights will require considerable adjustment of land holding institutions. The basic premise is that existing property right systems do not protect the rights of others. These latter rights are typically related to environmental concerns including water.

Water is characteristic in that it transfers a problem from one point to another and hence beyond the immediate concern of the polluter. Control needs to be exerted on the actions of the polluter to achieve standards which society deems desirable. Thus costs could be imposed on farmers to reduce pollution of waterways, and benefits in the form of clean water would be generated for society as a whole.

Under the Resource Management Act, local authorities are required to define outcomes that meet the purposes of the Act. Most important of these are the clauses requiring minimum standards of environmental protection (sub-clause b of the purposes clause). In some cases, society may have a view of absolute purity, ie no material in their drinking water whatsoever. The costs of achieiving this are normally met collectively.

To meet the required standard economic instruments could be used by the managing authority to achieve it. Polluters could be taxed for pollution above the bottom line or they could be required to pay for transferable permits, or possibly required to negotiate with affected community groups and compensate them for some agreed standards. Repetto (1980) assesses the relative merits of price and quantity-based instruments where the slope of the MC curve indicates whether to use a price or a quantity instrument.

From an economic point of view, the market process is clearly preferable. From the social point of view, the cooperation of the community would be preferable. It would be second best for the local administering authority to assume the role of setting standards though they may be highly tempted to do so.

Think of a free-draining catchment with excessive use of fertiliser. A solution might be to establish a market in fertiliser inputs (Reeve and-Kaine 1991). A set of traded permits in phosphorus use could be devised which did not exceed the absorptive capacity of the waterway and which could be adjusted to the total quantity of water available. In effect it would be a market in phosphate discharges. The authors claim that such a system would:

There are a wide range of environmental objectives that need to be addressed. A system is needed that deals with soil erosion, surface cover, burning, water quality, water discharge, pesticide use, noxious weeds, introduced animals and pests, tillage on slopes, and so on. The incidence of these differ from region to region.

There is a great deal of scientific work required to establish environmental standards covering all the desired outcomes. However, it may be that good practice rules could be derived that substitute for scientific criteria. There are great differences between point sources of degradation and non-point sources.

Existing institutional measures use a variety of instruments. Regulations are used in some areas and incentives in others. Collective administrative systems conceal the costs of regulatory and incentive schemes and few comparisions have been made of the alternatives. It is not clear at this stage which of the "bads" would be best suited to a polluter pays scheme such as Bromley and Hodge propose. Reeve and Kaine have outlined how a market could be established for farming inputs which create waterway pollution.

Regional and district councils will have the responsibility of setting environmental standards subject to national policy directives. They will have an obligation to consider all possible instruments and justify their selection as the most efficient (section 32). Some uniformity would be assured by consultation with neighbouring jurisdictions.

As it stands therefore the mix of incentives and regulations is in the hands of the local authorities. A proposal like Bromley and Hodge's would require more direction from the centre than is currently the fashion in New Zealand.

The property rights analysis brings out the crucial role of market solutions to resource management problems. The attenuation of private property rights was found to be justified because spillovers or externalities are common in agriculture. Scott's representation of interest in property rights is a useful descriptive tool but should remain subservient to the need for social control of environmentally sensitive inputs.

Non-attenuated property rights still have a role in guiding efficient use of resources within a well-defined social and institutional framework.

The property rights efficiency analysis does provide some insight into the rights established under the Torrens system of land registration. No one has established before that there is a direct connection between land use practices and the characteristics of property rights. The Torrens system is very efficient in doing what it is meant to do - providing absolute security at low cost. The registration system was designed before the recognition of technological externalities and hence does not provide any incentives to right holders to manage the externalities properly.

There is little evidence of assessment of relative transaction costs of different right systems. Some of this would be undertaken in backroom dialogue when respective merits of alternative plans were thrashed out. This may have to change as the Resource Management Act (section 32) does require any objective, rule or policy to have regard to the benefits and costs of the principal alternative means and effectiveness in achieving the objective or policy. There will be scope here for considerable discussion of the relevance of transaction costs and efficient solutions.

The Bromley and Hodge proposal involves defining a satisfactory institutional framework and developing satisfactory standards of performance. They then introduce the notion of a non-tradable permit for a departure from the standards at a suitable fee. It is not clear whether the fee would be scaled according to the degree of the departure from the norm. In effect, the proposal is a polluter-pays solution without transferability.Reeve and Kaine develop a transferable permit system for phosphate discharge into waterways with a scaled fee. The nonpoint discharge problem is overcome by estimating the external impact from fertiliser use. In a water basin, transferability is permissable because the total load of nutrients is the important parameter.

The latter proposal goes a long way to meeting the efficiency criteria laid down at the beginning of this paper. Individual initiative is retained by a relatively simple attenuation of an unfettered property right with fairly low transaction costs. Agronomic efficiency is enhanced and incentives created for investigating less polluting uses and management of fertiliser. Control of the nutrient load in waterways then brings about the desired social level of control of potential eutrophication and unsightly masses of stagnant water are not created.

In the end, the very complexity of the subject matter, and the relatively large number of interested parties who have to be consulted, will bring about new administrative systems which will be, at the very least, best effort approximations to the levels of optima described in this paper. Attention must focus on the administrative solutions that controlling authorities can devise that achieve environmental objectives while at the same time minimise the impact on efficiency and growth.

Alchian, A. and Demsetz, H. (1973), 'The Property Rights Paradigm', Journal of Economic History 33, 17-27.

Bradsen, J.R. (1988), Soil Conservation Legislation in Australia: Report for the National Soil Conservation Programme, University of Adelaide.

Bradsen, J.R. (1989) , 'Effectiveness of Soil Conservation Legislation across Australia', Fifth Australian Soil Conservation Conference, Perth, 10-15 September.

Bromley, D.W. and Hodge, I. (1990), 'Private Property Rights and Presumptive Policy Entitlements: Reconsidering the Premises of Rural Policy', European Review of Agricultural Economics 17, 197-214.

Castle, E.N. (1978), 'Property Rights and the Political Economy of Resource Scarcity', American Journal of Agricultural Economics 60(1), 1-9.

Cox, G., Lowe, P. and Winter, M. (1988), 'Private Rights and Public Responsibilities: the Prospects for Agricultural and Environmental Controls', Journal of Rural Studies 4, 323-337.

Dragun, A.K. (1989), 'Property Rights and Institutional Design' Workshop on Economics of Institutional Change, Lincoln College, New Zealand, February 10.

Hide, R.P. (1987), 'Property Rights and Natural Resource Policy', Studies in Resource Management No 3, Centre for Resource Management, Lincoln College, New Zealand.

Izac, A.M.N.(1986), 'Resource Policies, Property Rights and Conflicts of Interest', Australian Journal of Agricultural Economics 30, 23-37.

Jacobsen, V. (1991), 'Property Rights, Prices and Sustainability', Working Papers in Economics No 91/5, University of Waikato.

Jardine, V. and Scobie, G. (1990), 'Mining Policy: Rights and Wrongs', Proceedings of Annual Conference of New Zealand Branch Australian Agricultural Economics Society, Blenheim, 146-153.

Kirby, M.G. and Blyth, M.J. (1987), 'Economic Aspects of Land Degradation in Australia' Australian Journal of Agricultural Economics 31, 155-174.

Looney, J.W. (1991), 'Land Degradation in Australia: The Search for a Legal Remedy', Journal of Soil and Water Conservation July-August, 256-259.

Moore, W. and Arthur-Worsop, M. (1989), 'Privatising Water: An Analysis of Initiatives to Sell Community Irrigation Schemes and to Create Water Markets', Proceedings of Annual Conference of NZ Branch of Australian Agricultural Economics Society, Bulls, 93-110.

OECD, (1987), Pricing of Water Services, OECD Environment Committee, Paris.

Quiggin, J. (1986), 'Common Property, Private Property and Regulation: The Case of Dryland Salinity', Australian Journal of Agricultural Economics 30, 103-117.

Reeve, I. and Kaine, G. (1991), 'Ecosystem Coupled Markets: A Policy Approach for Sustainable Land Management', Proceedings of International Conference on Sustainable Land Management, International College of the Pacific, Palmerston North.

Repetto, R. (1980), 'Air Quality under the Clean Air, Act' , Incentives for Environmental Protection, Schelling, T.C. (ed.), MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 223-229.

Scott, A. (1989), 'Evolution of Individual Transferable Quotas as a Distinct Class of Property Right', in The Economics of Fishery Management in the Pacific Islands Region, ed.by Campbell H., Menz K., and Waugh G., ACIAR Bulletin No 26, Australian Centre for International Research, Canberra.

Young, M.D. (1992), Sustainable Investment and Resource Use, CSIRO, Canberra; and UNESCO, Paris; Parthenon, Carnforth, UK.