by

Robin Johnson2

1. The major dairy co-operative companies have been discussing industry

rationalisation for some years. In 1998 impetus was given by the then government's

policy of producer board reform. As early as 1996, savings of $250m had been

identified, and industry strategic plans were being drawn up. In 1998 a consultant's

report from McKinsey and Co. suggested that the direction the industry should take to

improve returns would be to expand offshore through mergers and acquisition, while

establishing onshore a Megaco-op. This would integrate the great majority, if not all, of

the processor co-operatives and the Dairy Board into a single united company

(Producer Board Project Team, briefing papers, p.6).

2. After dialogue with government and negotiations with industry leaders, the Dairy Industry Restructuring Act (DIRA) was developed and passed in September 1999. The Act addressed the key public policy issues relating to the proposed megacoop. If it had become effective, the DIRA would have:

3. The legislation only came into effect if the merger was approved by farmers, authorised by the Commerce Commission, and had become effective by September 1 2000. To establish the megacoop required the merger of co-operatives accounting for at least 75% of the shares in the Dairy Board (effectively a merger of at least two of the largest co-operatives, NZ Dairy Group and Kiwi Co-operative Dairies). A merger of the co-operatives required support of 75% of the votes cast, with votes held by supplier shareholders on a milk solids supplied basis (ibid, pp.6-7).

4. Thus, while the DIRA was enacted in 1999, its entry into force was dependent on

producer agreement to a megamerger of the main processing companies and

Commerce Commission authorisation of the merger (MAF briefing papers). Under the

Act, the Dairy Board's single desk powers were to be repealed from 1 September 2000,

and the new merged company (MergeCo

) would have the full right to export to

restricted markets for a period of six and a half years, phasing down over the following

four years. Following that, access was to be allocated by a new company (Quotaco

),

with the objective of maximising returns to its shareholders (who will be farmers,

initially at least).

5. The then government wanted to encourage reform of the producer board system and appeared to be offering powerful incentives to get the process started. While co- operative ownership of the Dairy Board had been established under the Dairy Board Amendment Act 1996, control over the quotas was needed to continue to exploit any existing trading advantage the Board held delegated responsibility for.

6. The industry's initial application to the Commerce Commission in mid 1999 received a negative draft determination and was subsequently withdrawn. The Commission considered that the anti-competitive costs outweighed the benefits. The Commission expressed particular concern that farmers would lack choice about whom they could supply milk to. They were also concerned that domestic consumers would have limited choice of suppliers of dairy products. The Commission noted that much of the asserted benefits were able to be gained without a megaco-op. The industry would have to address the Commission's concerns, including in particular the right for farmers to exit the megaco-op with the fair value of their capital, if the application was to be successful (Producer Board Project Team, p.9).

7. After the Commerce Commission draft determination, the two major companies entered into detailed discussions of a possible merger taking into account the Commission's views on domestic consumers2. Details of these discussions have not been made public though it is clear from remarks made by Graham Calvert, chairman of the mega-merger establishment board, that agreement could not be reached on the terms of the merger.

8. From various announcements, it appears that the establishment board had available

to it a report or series of reports setting out the benefits and costs of the merger under

various scenarios. In respect of these reports Mr Calvert said: There was such an

extraordinary difference in the balance sheets of the companies, and they had done

such different things. When you come to getting the 75 per cent farmer vote, you were

never going to get them to agree without a business plan

, and Kiwi has more

indebtedness and half the production. The Northland move [by Kiwi] would just

compound the problem

(The Dominion March 31, 2000).

9. So what were these mechanisms over which the companies could not agree? This paper sets out what I think are the corporate finance issues that crop up in the circumstances. These are derived from corporate finance books and not from the said reports which are not publicly available.

10. The basic aim of the firm is to increase company value. Company value

is the

extra wealth created by the activities of the firm. Normally the creation of wealth

appears on the equity side of the balance sheet. Profits before interest and tax (EBIT)

represents this concept. A more refined concept is Economic Value Added (EVA).

EVA is the profit/surplus after the full cost of capital has been accounted for. It is

defined as after-tax before-interest net operating profit

minus the cost of capital. The

cost

of capital is the weighted average cost of debt interest and the risk-adjusted

expected return on equity (WACC) as determined by the capital asset pricing model

(CAPM). Thus if a firm is creating economic value, its profit must exceed the true

opportunity cost of capital across the whole firm.

11. Market Value Added (MVA) measures how the market values the firm looking

forward. Other things being equal, MVA is the present value of the future stream of

value

as defined by EVA created by the firm.

12. Healy (2000) has noted that a high proportion of firms on the stock exchange in New Zealand have a negative EVA. Across the board, in recent years, this represents a tremendous loss of company value which some corporates do not appear to address. A similar exercise carried out on NZ sheep farms would show a similar result. Sheep farmers do not make enough profit to service their debt and earn a comparable return on their equity invested.

13. In the case of dairy companies, equity is held by the suppliers to the companies in a co-operative structure. The aim of maximising the increase in company value could therefore be expressed at one of several levels. First, the profit to the company after the opportunity cost of capital employed is accounted for (EVA); second, profit before interest and tax as in the EBIT model; and third, the operating surplus/profit available to suppliers for both their ownership of equity and their raw material supplied.

14. Now it is characteristic of co-operatives that their balance sheets do not distinguish

between the rewards to equity and the rewards for raw materials. In fact, as Hussey and

the Round Table (1992) have pointed out a number of times, the two returns are

bundled

together in the payout system used. This has serious implications for

resource use decisions when the individual prices are not known. Bundling also makes

it difficult to sort out the costs and benefits of a merger proposal.

15. In the absence of information from the co-operatives themselves we have to speculate what the basis of estimating shareholder value might be.

16. The situation is that two separate co-operative companies' balance sheets have to be merged together and equity issues in that merger addressed. Equity is taken to be represented by shareholder value before and after the merger. Shareholder value is defined as the addition to equity of the respective company, i.e. earnings before interest and tax. In this formulation, total capital cost has yet to be addressed and will be a mixture of debt and equity returns. If one company holds more debt than the other, then the proportion of profit available for return to shareholders is going to be less.

17. One company may pursue a high debt regime so as to enjoy the tax benefits on interest charges (and enjoy greater growth more quickly). Another company may prefer to work on a high equity-low borrowing base and forgo the tax benefits available as well as some potential growth. The tax benefits can be considered a government contribution to a company's investment programme - the so-called tax shield. These considerations then have a bearing on the weighted cost of capital for the EVA calculation.

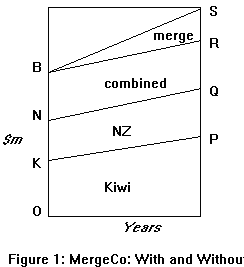

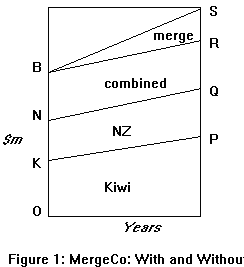

18. The merger process itself involves a comparison of what each company would have achieved without the merger compared with what would be achieved with the merger. It is therefore necessary to construct the with-and-without situation in terms of company value. Consider Figure 1.

Let ON = NZ Dairy Group current profit before interest and tax;

OK = Kiwi current profit;

OB = combined current profit.

Let KP = growth of Kiwi profit as a stand-alone;

NQ = growth of NZDG as a stand-alone;

BR = combined growth path;

BS = growth of MergeCo.

Then the present value of the added value stream KP is the current estimate of company value in the Kiwi company before interest and tax;

the present value of NQ is the current estimate of company value in NZDC; and

the present value of BS is the current estimate of merged company value.

19. Then the with-and-without situation is:

for Kiwi pv of BS - pv of KP,

for NZDG pv of BS - pv of NQ

Now if the prospects for one company on its own are better than the other company, apart from size considerations, then the merger favours the lower prospects company. This is because in the merged company all shareholders would be treated equally in terms of payouts etc. This is inherent in the structure of co-operative companies. Payout will be in proportion to the raw materials supplied. If there is an inequality between the two companies then some sharing arrangement is needed for sharing the benefits of the merger. In the case of Tui and Kiwi, and Kiwi and Northland, this took the form of a cash payment from the lower prospects company to the higher prospects company (The alternative would be to go down the path of a share swap in the registered company case, i.e. one Kiwi share is swapped for 1.2 Tui shares; but dairy companies do not have market valued shares!)4 .

20. Now since we do not have all the details of the projected growth paths of the existing co-operatives, their relative earnings, and the growth path and earnings of the merger, it would be futile to try and assess the details that go to make up the company earnings profiles. There is a certain amount of information around though, such as:

* debt servicing per kg ms is higher in Kiwi

* local market prospects tend to favour Kiwi

* size of operation and cost efficiencies favour NZDG

* terms of Tui merger with Kiwi

* terms of Northland merger with Kiwi

* terms of NZDG merger with South Island Dairy Co-operative.

21. The differences in size and trading returns in the two companies for the 1998-99 season can be seen in Table 1. In terms of milk solids (ms) delivered, Kiwi is about 5/8ths the size of NZDG. There is a big discrepancy in earnings (EBIT) which is due to different policies with regard to payments to suppliers. Operating profit before payment to suppliers looks to be a more comparable measure of performance. Production and revenue was much higher in the 1999-00 season.

| Table 1: The Two Companies (1998-99) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Measures: | Kiwi | NZDC | |

| Milk solids | mkg | 249.8 | 386.1 |

| Capital | m $ | 1630 | 1649 |

| Turnover | m $ | 1755 | 2451 |

| Operating profit* | m $ | 930 | 1611 |

| Earnings (ebit) | m $ | 33.6 | 176.0 |

| Staff | no. | 3455 | 3739 |

| Suppliers | no. | 4227 | 6696 |

| Cows | th. | 874.8 | - |

| * Operating profit before payment to suppliers | |||

| Balance Sheet Items: | |||

| Shareholders funds | m $ | 744 | 876 |

| Total assets | m $ | 1630 | 1649 |

| Per cent | % | 45.6 | 53.1 |

| Assets held as: | |||

| Cash/Inventory | m $ | 313 | 381 |

| Property/Plant | m $ | 909 | 890 |

| DB shares**etc | m $ | 383 | 358 |

| Other | m $ | 25 | 19 |

| Total | m $ | 1630 | 1649 |

| Liabilities: | |||

| Term loans | m $ | 521 | 347 |

| Overdraft | m $ | 4 | - |

| Owing to suppliers | m $ | 278 | 253 |

| Creditors/Payables | m $ | 83 | 174 |

| Total | m $ | 886 | 774 |

| Debt servicing: | m $ | 44 | 30 |

| Cost per kg ms | cents/kg | 17.6 | 7.6 |

| Rate of Interest | % | 8.4 | 8.6 |

| ** Kiwi shares @ $1.7 and NZDC shares @ $1.0 | |||

| Sources: Annual Reports for 1998-99 | |||

22. It appears that in the co-operative system, EBIT is what you make of it. Table 2 shows the relationship of EBIT in both companies in 1998-99 to what I have called gross return to shareholders. It appears that company payouts to farmers for milk solids have been financed in entirely different ways hence giving quite different estimates of profit trends.

| Table 2: Structure of Gross Return to Shareholders | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial item | Kiwi | NZDG | |

| Profit/Loss before tax | $ m | (9.835) | 146.369 |

| Interest | $ m | 43.473 | 29.656 |

| EBIT | $ m | 33.638 | 176.025 |

| EVA* | $ m | (102.0) | 34.2 |

| Payment to suppliers | $ m | 896.402 | 1434.780 |

| Payment to suppliers | cents/kg | 362 | 363 |

| Gross return to shareholders | $ m | 930.040 | 1610.805 |

| Gross return to shareholders | cents/kg | 372 | 417 |

| * EVA = cost of total capital @ borrowing rate. | |||

As might be expected, EVA is negative for Kiwi in that year, but NZDG was well in the clear. For the record, the EVA entity was worth minus 41 cents per kg ms in Kiwi and +9 cents per kg ms for NZDG.

23. It has been stated that the benefits of the merger are $300m per year in present value terms. It is not clear how many years it will take to get to that level. This is said to be an EBIT measure. So let us assume that NZDC can earn an additional $50 m per year and Kiwi an additional $75 m per year and both growing. (Assumption is that after the merger, all suppliers are treated equally). If we assume that the growth rate is 10% per cent per year and the discount rate is also 10% per year, then the increase in company value for NZDG is approx $500m (in present value terms) and that of Kiwi $750m. Spread over the 1998-99 combined output of 636m kg ms the differential is about 40 cents/kg ms.

24. That is, Kiwi suppliers stand to gain more from the merger than those of NZDG. Therefore NZDG directors would argue that Kiwi shareholders should pay for the privilege of joining the merger (Remember that is what Kiwi did to Tui). Thus NZDG is said to have made an offer to Kiwi that it would agree to the merger if Kiwi paid NZDG 40cents per kg of milksolids supplied! This Kiwi refused to do.

25. It may be that $250m is the net advantage to Kiwi in the merger. They gain more from the merger. Since it is a benefit generated by the merger, should Kiwi share the net benefit with NZDG? That is, they give NZDG only 20 cents of the advantage and keep 20 cents! Since 40 cents is the figure given to me by the managers it may be that the net advantage to Kiwi was 80 cents and a half way split would produce the compromise 40 cents!

26. The terms of the Tui-Kiwi merger appear to be that Tui suppliers would have 50 cents per kg ms taken out of their payouts over 3 years to make up this kind of compensation payment. For 1998-99 ex-Tui suppliers were paid $3.52 kg ms and suppliers other than ex Tui suppliers $3.62 (Annual Report p.34). On the face of it, the compensation was not paid directly to Kiwi shareholders but passed through the books of the merged company as a payout differential. The more recent agreement between Kiwi and the Northland Cooperative Company involves a 40 cents transfer, which presumably will be treated in the same way.

27. The terms of the merger of NZDG and the South Island Dairy Co-operative, effective 31 May 1999, included a divestment to NZDG shareholders of a 50% interest in NZ Dairy Foods. The interest was in the form of Class B shares. These shares carry an entitlement to half the dividends declared by NZ Dairy Foods. At the same time, eligible NZDG shareholders received a one-off $80m payment in July 1999 which equates to approximately 19.5 cents per kg of ms (Annual Report 1998-99, pp.28, 50). The latter appears to be a form of compensation to the existing shareholders before a merging of the books which has yet to go through the merged NZDG books.

28. As a side issue, the way these payments are made affects their tax status. In the Tui case, the payment passes through the payout system and appears as farm revenue (or farm revenue foregone). In effect, the transfer becomes a tax deductible expense for both sides. A capital payment to Kiwi shareholders would be tax free. In this case the transfer would have cost Tui shareholders even more! Presumably these concerns apply to any merger situation.

29. I am not entirely clear how the differential between the companies arises. In 1998- 99 the cost differential of interest on borrowings was worth 10 cents/kg/ms (Kiwi had been funding capital development by borrowing while NZDG had been ploughing back its profits). The margin in operating costs (pre payout) was 73 cents/kg/ms in favour of NZDG (but is there a different mix of products and processing costs involved?). Total revenue per kg ms favoured Kiwi by over 60 cents/kg/ms. These rough figures suggest a margin in favour of NZDG of around 13 cents/kg/ms based on the 1998-99 returns. What is important, of course, is the trends of these items in the future, taking into account mergers which have taken place since that date.

30. Since writing this last paragraph, Kiwi have announced their annual payout for 1999-00 (The Dominion, June 21). Kiwi posted a record payout of $3.82/kg/ms which included a record company premium of 47cents/kg/ms. Kiwi processed 382m kg ms and reached a record turnover of $2.6b. Presumably this was the influence of the Northland merger which took place during the year.

31. Discussion with executives of NZDG put down the failure of the merger discussions to a number of broader issues which went beyond the mere details of the balance sheet calculations. The merger documents required some assessment of future trends. But establishing the current position of the companies was compounded by problems associated with the effects of the recent changes in the industry on any assessment, e.g.

* absorbing the South Island Dairy Coop merger into NZDG' s books;

* absorbing the Northland merger into Kiwi's books;

* absorbing Food Solutions (Huttons) purchase by Kiwi;

* changes in the payment system introduced in 1999/00 (shift from cost

* engineering to 9 product categories said to be marginally priced).

The two companies also have different views on the reform of co-operative principles and have differently paced programmes of capital development.

32. The information available suggests that NZDG was pursuing a more corporate

model in the merged company. In particular the McKinsey report envisaged a future

where outside capital would be brought in and the equity shared with other interests.

In turn this would require a full unbundling of the payout system. The Kiwi company

appeared to want to retain the co-operative system with its emphasis on farmer control,

maximum payouts to suppliers, and continued bundling of payouts. It [the business

plan] didn't say where we got the money from for acquisitions overseas, or what we

were going to buy

(Calvert). These are large philosophic differences to overcome.

33. This paper is only about the analytics of the merger process and not about deregulation per se. Obviously other issues are important like the attitudes of Ministers, the views of the Commerce Commission, the uniqueness of the Dairy Board, and the presence of competitors in the wings. It will be interesting to see what emerges at the end of the day.

Healy, J.C. (2000), The EVA Forum: the Shareholder Value Performance of Corporate New Zealand, ANZ Investment Bank, Auckland.

Hussey, D.D. (1992), Agricultural Marketing Regulation, Reality versus Doctrine, a report prepared for the Business Round Table.

1) Paper prepared for Winter Meeting of the New Zealand Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, Blenheim, July, 2000. I am grateful to Graham Milne and Stuart Murray at NZDG for a briefing on the issues discussed. Bryan Smith (MAF) has provided useful comments on the draft.

2) Consulting Economist, Wellington (johnsonr1@paradise.net.nz)

3) It is understood that the two companies had taken into consideration the need for shareholders to receive a fair entry and exit value for their shares. This would be critical to ensuring that there was at least the threat of competition in the market for raw milk supplies.

4) Bryan Smith points out that the key limiting factor on a share swap is the definition

of a qualifying company

under the Dairy Board Act. Under the Act a dairy

coopersative must issue shares to its suppliers in proportion to the milksolids they

supply to the cooperative in order to qualify for Dairy Board shares.